Why hamstring flexibility is important and how to achieve it rapidly.

Written by Peter Georgilopoulos, APA Sports Physiotherapist

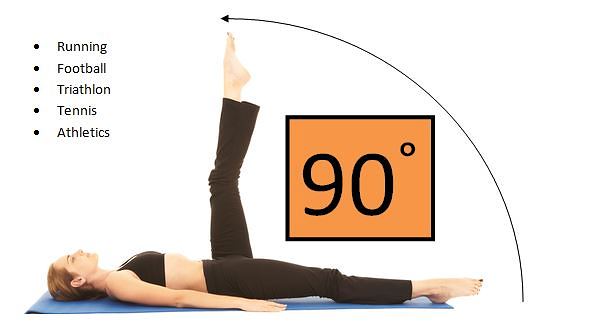

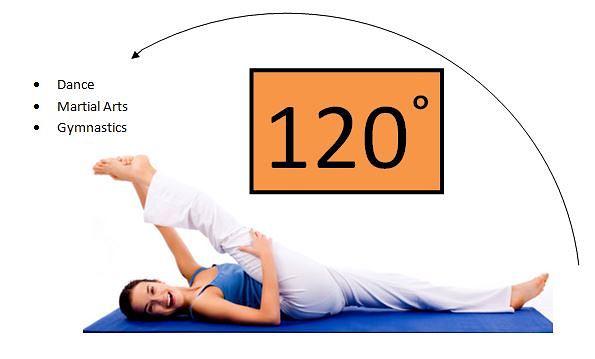

Hamstring flexibility is highly desirable in most sports involving running and is an integral part of activities such as dancing, gymnastics and martial arts.

The desire for hamstring flexibility in running sports is primarily aimed at reducing muscle tears or strains and improving running efficiency, agility and speed.

Running with tight hamstrings is analogous to driving a car with the hand brake partly engaged- the vehicle still moves forward but performance is impaired, fuel [energy] efficiency is reduced and there is increased friction between moving parts which leads to early and preventable breakdown.

Hamstring flexibility, of course, is one of the primary judging criteria in dance and gymnastics so success in these disciplines is very much dependant on knowing how to restore flexibility even following excessive muscle loading leading to tightness .

What is often poorly understood about poor hamstring flexibility, is that it is a major driver in anterior knee pain in which the articular surface [the undersurface] of the knee cap [patella] is gradually eroded. This leads to a throbbing ache aggravated by activities that involve compressing the patella against the articular surface of the thigh bone [femur]. Provocative activities include ascending or descending stairs, squatting , driving a car in which the affected leg is lifted to engage the brake or even sitting for prolonged periods in which the affected surface of the patella is compressed against the knee joint by the stretched quadriceps [thigh] muscles.

This vital contributing factor underlying anterior knee pain is frequently missed often leading to long term use of analgesics and anti- inflammatory medication as well as extensive [and expensive] medical and rehabilitation sessions.

Hamstring tension is also an integral contributor to maintaining an upright posture with increased hamstring tightness leading to pelvic rotation. Exaggerated curvature in the lower back causes increased compression in the lumbar [lower back] weight-bearing joints known as the facet joints which in turn precipitates early osteo- arthritis of the spine.

All in all, there are many good reasons to achieve optimal hamstring flexibility even if you are not a runner, dancer or gymnast. You may just find that you have unravelled the cause of your chronic low back pain and rediscovered freedom of movement!

So how much flexibility should you be aiming for and how can you assess it?

These are only guidelines and whereas some people may have little difficulty achieving these targets, in most cases [especially where recurrent injury is concerned] it becomes glaringly obvious that the symptomatic side is often significantly restricted.

Often, restoring symmetrical flexibility is enough to immediately alleviate unilateral knee pain, back pain and calf or groin tightness as all these structures are supplied by a common nerve and its branches which we know as the sciatic nerve.

The ability to successfully restore hamstring flexibility [or any muscle for that matter] revolves around 3 factors:

- The physical tensile capacity of that muscle and tendon unit, in other words, how far can we physically stretch this elastic structure before it starts to tear?

- Whether the associated joints providing the movement have full available range. ie In the case of osteoarthritis of the hip joint it may not be physically possible to stretch the hamstring to its full range simply because the hip joint is unable to achieve sufficient range to place the muscle on stretch.

- Most importantly, eliminating the effect of the sciatic nerve on the tension of the hamstring muscle. The reason why I refer to this factor as the “most important” is because it is the one variable that can be altered almost immediately. Eliminating the neural [nerve] component can yield remarkable gains in hamstring flexibility in a matter of minutes compared to the many weeks of daily flexibility work traditionally undertaken.

So why aren’t we looking at methods of achieving immediate results?

The good news is that the clinical methods that I have used to facilitate rapid flexibility for three decades have been strongly supported by two randomised controlled research trials which I undertook in 2010 and 2011. The findings were published and presented at various conferences including the National APA Conference in 2012. This study compared static stretching of the posterior thigh muscles to spinal mobilisation in which spinal mobilisation proved to be significantlysuperior in achieving immediate results.

Pre mobilisation Post mobilisation

Spinal mobilisation techniques alleviate spinal stiffness which appear to reduce irritation of the adjoining nerve roots supplying the muscles of the buttock, groin and posterior thigh. Without adverse stimulation of the nerves, the supplied muscles are able to achieve a fully relaxed state allowing immediate improved stretch.

I have consistently shown that by setting flexibility objectives of at least 90°in sports teams, hamstring and groin injuries have reduced by more than half.

The difficulty in this approach is that it requires the manual skills of a physiotherapist which is easily accessible in a professional sports team but is unattainable for most people.

So how can you utilise this system on a daily basis?

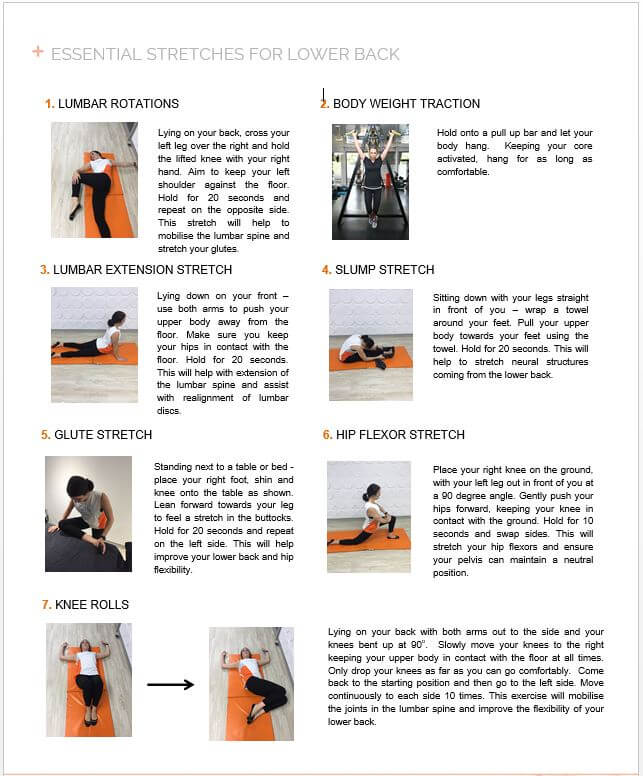

[1] Commence your stretching session by starting with your spine. Use a massage ball to target tight structures on either side of your spine and progress to both buttocks.

[2] Target muscles in your pelvis and spine with the following specific stretches before commencing on your normal stretching drill for the muscles in your lower limbs and enjoy improved performance and less risk of injury!

Click here to download and print off the exercise sheet below.